Researchers in the Mitchell lab have found that cancer cells can hijack DNA normally used when tissues and organs are formed to enhance tumour growth. The pathway they found is active in multiple cancer tissues, showing that this mechanism is relevant for many types of cancers.

Researchers in the Mitchell lab have found that cancer cells can hijack DNA normally used when tissues and organs are formed to enhance tumour growth. The pathway they found is active in multiple cancer tissues, showing that this mechanism is relevant for many types of cancers.

The human genome is amazingly complex, containing both genes and instructions to turn genes on and off in different contexts. “The genome is like a recipe book written in DNA that gives instructions on making all the parts of the body.” explains co-author Dr. Luís Abatti. “In each organ, only the recipes relevant to that organ should be open, whether it’s lung or breast or some other tissue.

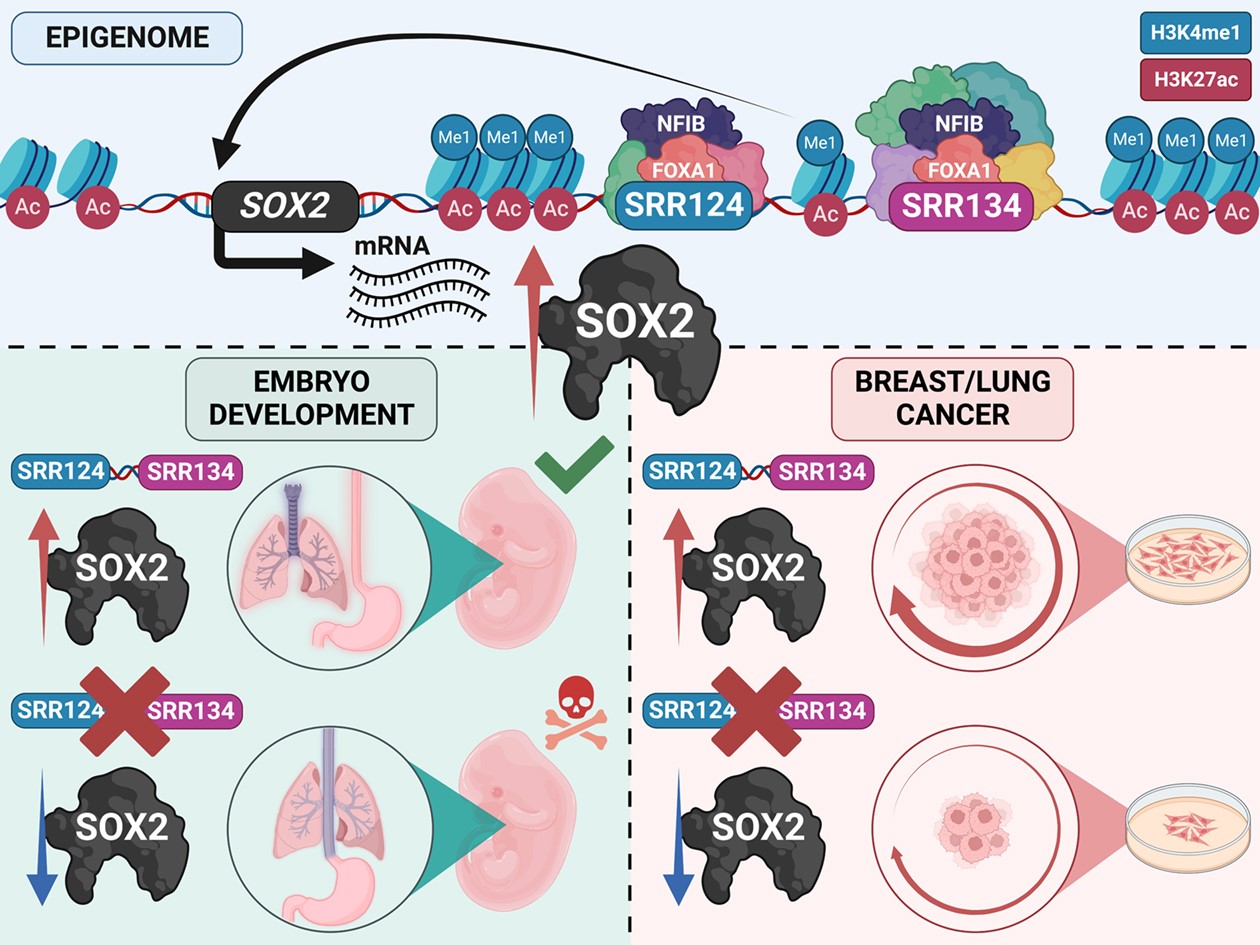

We found some cancer cells were opening the wrong pages in their book, one that contains the SOX2 gene, which is normally needed in many types of stem cells but can also cause tumours to grow in an uncontrolled way.”

The UofT researchers analyzed genome data to look for an ‘enhancer’ region that could activate SOX2 in stem cells and in cancer cells. The enhancer they found could activate SOX2 but it was not open in stem cells.

Instead, they found that the enhancer was open in many different types of patient tumours meaning this could be a “cancer enhancer” active in bladder, uterus, breast and lung tumours. Unlike many cancer-causing changes, this mechanism does not arise out of mutation due to DNA damage but instead is caused by this part of the genome becoming more open when it should be staying closed.

The researchers wondered if cancer cells had increased growth due to this enhancer. When they removed the enhancer in lab-grown cells, the cancer cells were defective at creating new tumour colonies.

“Having figured this out, an important question remained: why our cells would have this region of DNA that makes cancer worse?” asserts co-author Prof. Jennifer Mitchell. “We found that removing this region from the genome of mice caused an airway defect; these mice do not form a separate passage for air and food in their throat as they develop”.

So this potentially dangerous “cancer enhancer” region is likely in our genomes to regulate this same process during human development. However, if a developing cancer cell opens up this region, it will form a tumour that grows more quickly and is more dangerous for the patient.

“Now that we know how the SOX2 gene gets turned on in these types of cancers we can look at why this is happening. To use Luís’ analogy, how did the cancer cells end up on the wrong page of the recipe book? Something really interesting that we found is that two proteins that were known to have a role in the developing airways (FOXA1 and NFIB) are now regulating SOX2 in breast cancer.”

The enhancer is activated by the FOXA1 protein and suppressed by the NFIB protein. That means that drugs suppressing FOXA1 or activating NFIB may lead to improved treatments for bladder, uterus, breast and lung cancer where the enhancer is open.

This research is published as a Breakthrough Article in Nucleic Acids Research as “Epigenetic reprogramming of a distal developmental enhancer cluster drives SOX2 overexpression in breast and lung adenocarcinoma”