Sugar-coated cells’ surprise role in gastrulation

The way embryonic cells stick to each other is given a new twist by studies of the sugar coating around developing tissues. The Winklbauer lab has shown that the glycocalyx sugar coat mediates cell-cell attachment across significantly large distances between cells. These surprising results are published in the journal PNAS as “Cell-cell contact landscapes in Xenopus gastrula tissues”.

Debanjan Barua began graduate studies in Prof Rudolf Winklbauer’s lab by studying Brachet’s cleft, a tissue-boundary in the frog embryo where the migrating mesoderm tissue travels adjacent to structured roof ectoderm. Most studies on cell-cell adhesion in the embryo focus on cadherin, which allows cells to sense each other over short distances. Scientists can clearly detect these interactions in monolayered tissues where individual cells are connected across relatively short distances.

However, in multilayered tissues undergoing rapid cell-cell rearrangement (as in Brachet’s Cleft tissues), cell-cell interactions seem amorphous. Barua worked to describe the landscape of these interactions and identify the adhesion components involved.

On the cell surface of embryonic tissue is a fibrous mesh called glycocalyx, which is composed of different sugar compounds. It is often described as a barrier to cell-cell adhesion in that the large size of its components hinder interactions between cells. It has a net negative charge, which Barua exploited by staining the cells with positively charged, electron-dense lanthanum to visualize the glycocalyx.

He was excited to observe the long, chain-like molecules of the glycocalyx interpenetrating across the gap between adjacent cells, contradicting the view of glycocalyx as a barrier. To explore the function of glycocalyx in cell-cell attachment, Barua assessed the geometrical angle and distance of gaps between cells to map the spectrum of interaction in normal embryos compared embryos where he disrupted gene expression.

Barua disrupted several transmembrane glycocalyx components such as syndecans, which are known to mediate adhesion with the extracellular matrix. In his study, syndecan depletion caused jagged gaps between cells, reducing cell-cell contacts to small points, but with less effect on cell density. This shows that syndecans play a role in cell-cell adhesion distinct from cadherins, which result in wide, long gaps when depleted. Moreover, his ground-breaking results showed that each component of the glycocalyx is unique in its modulation of cell-cell contacts in these tissues.

Having revealed a new element of embryonic development, Barua earned his PhD by virtually defending his thesis in 2021: "I could not have done it without Rudi [Winklbauer] showing me how to think about and approach my data". Barua advises graduate students to take a break from collecting data to think about what their data means, as this tactic greatly benefited his studies. He is currently continuing his work in the Winklbauer lab by studying how ephrin signaling controls tissue separation at Brachet’s cleft and will begin his postdoctoral studies next year.

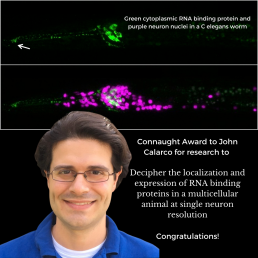

Calarco Lab receives Connaught Award to map RNA binding proteins in the nervous system

Professor John Calarco has been granted a Connaught New Researcher Award to publish a detailed atlas of RNA binding proteins (RBPs), key regulators of gene expression, in the nervous system of the roundworm C. elegans. Mutations in RBP genes are thought to be associated with diseases including cancer and neurological disorders, so this atlas will provide insights into how those conditions can develop.

As a gene is read from the DNA blueprint of the cell, it produces a long primary RNA transcript that must be processed to a shorter mRNA. RBPs work together to guide RNA processing to produce mRNA, and ultimately translated protein, in the amounts that the cell needs. Calarco has identified over one hundred RBPs expressed in the nervous system of C. elegans. Undeterred by this large number, he will combine available resources and CRISPR technology to label specific RBPs with fluorescent protein tags.

A further challenge in studying the function of these proteins is that they have variable abundance in different cells and only bind to specific RNAs. Many RNA transcripts are also recognized by different cocktails of RBPs through defined sequences, so they can only be processed correctly by one or multiple combinations of specific RBPs.

Finally, it is important to understand the subcellular locations of RBPs, because they are active in RNA processing and metabolism both in the nucleus and cytoplasm. This finely tuned regulation of RNA processing by RBPs is key to how the diverse cell types in the nervous system work together to respond to external stimuli and drive behavioral responses.

Calarco’s lab in the Department of Cell & Systems Biology will use advanced microscopy techniques to create an atlas with the precise location of specific labelled RBPs within each cell of the C. elegans nervous system. By combining information on RBP location with expression of genes containing RBP-binding sequences, a deeper understanding into the evolution of neuronal diversity and a more accurate representation of gene expression in the nervous system can be developed.

The Connaught New Researcher Award serves to foster excellence in research and innovation by providing support for new University of Toronto faculty members who are launching their academic careers. These awards are intended to establish a strong research program, thereby increasing the faculty member's competitiveness for external funding.

“Receiving the Connaught Award has provided a much-appreciated source of seed funding to advance the goals of this ambitious project." says Calarco, "Particularly, it has enabled me to recruit new trainees to work alongside my postdoctoral fellow Dr John Laver, who has been a major driving force in advancing this study. With this support from the University of Toronto, we are now certain to bring the first phase of our project to its completion, which is very exciting for us!”

Congratulations, Professor Calarco!

Sustainability in the Earth Sciences Centre

Settled on top of UofT’s Earth Sciences Centre on Huron Street are fifteen greenhouse zones for CSB and EEB researchers. High energy sodium lamps provide light to grow cultivated plants, but a new sustainability project is underway to replace these lamps with energy efficient LEDs.

Settled on top of UofT’s Earth Sciences Centre on Huron Street are fifteen greenhouse zones for CSB and EEB researchers. High energy sodium lamps provide light to grow cultivated plants, but a new sustainability project is underway to replace these lamps with energy efficient LEDs.

The Earth Sciences greenhouses contain specimens of hundreds of plants in specialized environments to mimic desert, tropical and temperate zones. These samples are used to understand cell biology, ecology and evolution in plants and often require high intensity light to flourish. When Earth Sciences was built in 1989, yellow sodium lamps provided the needed intensity, but these old lamps have poor energy efficiency.

A pilot project by Chief Horticulturalist Bill Cole to replace sodium lamps with LED panels has produced excellent results in one greenhouse. Cole says that “They look great and produce a high intensity balanced spectrum light. Ten 600W LED fixtures produce more light and are more energy efficient than fifteen 465W sodium vapour lights.”

Direct energy savings are accompanied by additional benefits. The colour balance for the full spectrum LED lights is better for the plants, providing more red and blue wavelengths. The new lights produce less radiant heat which will also reduce the burden of cooling for the greenhouses. Cole has recommended proceeding with full replacement in all fifteen greenhouses planted on top of the Earth Sciences Centre.

Direct energy savings are accompanied by additional benefits. The colour balance for the full spectrum LED lights is better for the plants, providing more red and blue wavelengths. The new lights produce less radiant heat which will also reduce the burden of cooling for the greenhouses. Cole has recommended proceeding with full replacement in all fifteen greenhouses planted on top of the Earth Sciences Centre.

Funding for this project came from greenhouse operating funds, with support from CSB and EEB to arrange installation. A similar project in labs and offices of the nearby Ramsay Wright Building reduced energy consumption by 380,000 kilowatt hours annually. As the yellow glow above Earth Sciences transitions to a more even hue, UofT can count on even greater savings.

Alice DesRoches is 2021's Nyman Scholar

Alice DesRoches has earned the 2021 Dr Leslie Paul Nyman Scholarship by demonstrating exceptional leadership skills in the community and a strong commitment to plant biology. DesRoches was an active peer member of her First and Second-Year Learning Communities (F/SLC) and is incoming Executive Director of the Sexual Education Centre (SEC). She excelled in plant biology courses BIO220 and CSB350 and is conducting research in Prof Art Weis’ laboratory.

DesRoches values the opportunities provided by the F/SLC program, where student peers build effective academic habits. “I came to UofT from the US with virtually no connections here, so I appreciated the support, the introduction to research experiences as well as the consideration for prioritizing one’s mental health.

As a Volunteer Coordinator and incoming Executive Director of the SEC, DesRoches has made community service a priority during her undergraduate studies and has stood out for her natural ability to lead, mentor, and support others. She feels that “Peer support isn’t about knowing everything but about giving the best advice you can. You need to be compassionate about the situation others may find themselves in but be able to step back and refer them to other services if necessary.”

An early interest in paleontology led to a fascination with biology. In high school, DesRoches was further inspired to study the subject by her AP Biology teacher Mr. Boylan, who instilled a sense of wonderment at intricacy of molecular biology.

The second year BIO220 lab course as well as CSB353 encouraged DesRoches’ interest in plant biology and she joined the Weis lab as an ROP project student, assisting with evolutionary biology-related projects. Her work included caring for Brassica rapa plants in the Earth Sciences greenhouses and collecting data in ongoing seed aging experiments. DesRoches plans continue her research in the Weis Lab in her final year, focusing on genetic dominance in flowering time.

For other students interested in plant biology, DesRoches advises that “CSB350 is a really great, hands-on course. The course material draws directly from molecular plant biology research by Prof Christendat and Prof Nambara, so it’s a really valuable experience.”

Congratulations Alice DesRoches!

Finding Fulfillment in a Fine Lecture with Prof Kenneth Yip

Prof Kenneth Yip learned early in his career that he really enjoys teaching from giving classes as a post-doctoral researcher. “I love to see that students are excited about science and I enjoy hearing questions that show they understand the material and are eager to learn more. My favourite feeling is finishing a lecture that I know has been well understood!” Yip’s dedication has earned him a promotion to Assistant Professor in the Department of Cell & Systems Biology.

Yip is often the first professor for life sciences students in the introductory BIO130 course, who may encounter him again in second year Biotechnology or third year Cellular Dynamics courses. He structures his lessons to be clear and easy to understand with anecdotes about the process of scientific discovery. His teaching techniques use evidence-based strategies to improve student success and have made him a favourite instructor for many students.

Yip’s research at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre means that his students learn the latest advances in molecular and cell biology. He is proud that his recent research revealed a new mechanism of radiation-induced fibrosis, and allowed development of drugs to regulate the metabolic dysregulation behind this syndrome. In addition to practical bench skills, Yip has expanded his knowledge by studying regulatory compliance, bioethics, and online instruction techniques. A further biological phenomenon that Yip craves is the rumble deep in his body that comes from watching Formula One racing.

Graduate Teaching Assistants who provide a more personal approach to the thousands of students who take introductory biology rely on Yip for guidance on their teaching. He mentors these TAs by encouraging them to think about what they want to achieve through the course, by guiding the more mature senior students to lead their peers, and by helping them with CVs and applications.

Yip works closely with Prof Melody Neumann on testing innovative pedagogical techniques in the classroom. He wants to use the freedom afforded by his new appointment to build on these collaborations and develop some of his own innovations. Congratulations, Professor Yip!

Congratulations to our new Faculty!

Cell & Systems Biology has Professors in three newly appointed posts starting on July 1, 2021!

Professor Shelley Lumba has been appointed as Assistant Professor in Plant Systems Biology at Cell and Systems Biology. Lumba studies molecular mechanisms of dormancy and germination in plants in the Earth Sciences Building. Her lab uses systems biology approaches to generate signalling networks underlying germination in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana and in parasitic plants, such as Striga hermonthica. She was formerly a contractually limited term appointment, but will now qualify to apply for tenure.

Professor Kenneth Yip has been appointed as an Assistant Professor, Teaching Stream. He has been a Sessional Lecturer for foundational biology courses BIO130 and BIO230 over many years at UofT, as well as instructing advanced third- and fourth-year courses. Yip is the recipient of the Faculty of Arts and Science Superior Sessional Instructor Teaching Award. He conducts research at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in cancer drug discovery and translational genomics.

Professor Ritu Sarpal has been appointed as an Assistant Professor, Teaching Stream. She has been teaching advanced courses in the Stem Cells and Developmental Biology Program as a Sessional Lecturer. Sarpal conducts research in the Ramsay Wright Building on the mechanisms that allow epithelial cells to adhere to each other, as well as supervising undergraduate project students.

Congratulations, Professors!

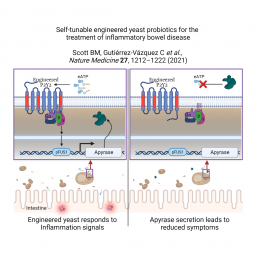

Synthetic biology circuit from Chang lab may lead to IBD treatment

A new probiotic yeast, engineered at the University of Toronto and extensively tested at Bringham & Women’s Hospital (BWH) was designed using synthetic biology to sense and respond to inflammation, and has been shown to reduce IBD in mice. Inflammation can be a healthy response to infection that helps our bodies to recover, but chronic inflammation can cause long term problems like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Existing IBD treatments inhibit inflammation throughout the body regardless of where and when inflammation occurs, which can lead to significant side effects.

In developing this treatment, Benjamin Scott, a PhD student at CSB in the Chang and Peisajovich labs, noted reports of elevated levels of extracellular ATP (eATP) during inflammation and reasoned that detecting and responding to eATP could balance pro- and anti-inflammatory signals. He benefited from the expertise of Prof Chang, a leading expert in GPCR proteins. GPCRs function as sensors for a variety of molecules, including those that are present during inflammation in the intestine. GPCRs are used in engineered yeast cells to understand the ways genes are activated and more recently for the circuitry of synthetic biology.

Scott started his experiments by adding a human GPCR protein known as P2Y2 into yeast to detect eATP. He engineered the P2Y2 yeast to turn on a second synthetic component, a red fluorescent protein, if P2Y2 detected eATP. In his first tests, the crimson colour was only seen at extremely high levels of eATP. To improve human P2Y2’s sensitivity, protein variants were randomly generated and the reddest yeast revealed P2Y2 variants that could detect levels of eATP found in inflamed tissue.

With the ability to detect levels of eATP found in the body, Scott could now turn to ways of reducing the levels of eATP around the yeast cells. An enzyme called apyrase breaks down eATP, so Scott swapped out the red fluorescent protein for potato apyrase, the most active apyrase known. The resulting yeast strains were successful at both detecting and reducing pro-inflammatory levels of eATP in a test tube.

Demonstrating reduced intestinal inflammation still required testing in an animal model. Peisajovich and his long-time friend Prof Francisco Quintana (BWH) were developing the idea of a “living drug”, engineered cells that produce therapeutic effects. Work moved to Quintana’s lab, which studies autoimmune diseases using mice. Dr. Cristina Gutiérrez-Vázquez and others in the Quintana lab undertook the treatment of lab mice with the engineered yeast. She demonstrated that there were no negative effects on normal intestine, and that the engineered yeast was cleared out of the mouse’s gut within 24 hours.

Her detailed analysis of intestinal inflammation demonstrated the ability of the engineered yeast to reduce inflammation, a key step in alleviating inflammatory bowel diseases. This was a huge result that the labs celebrated, and they filed a patent for their demonstrated probiotic based on these results.

Their work is published in Nature Medicine as “Self-tunable engineered yeast probiotics for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease”.

Developing Excellent Science Brings Dr Ritu Sarpal a Faculty Appointment

Developmental Biologist Dr Ritu Sarpal’s dedication to teaching and training has earned her a position as Assistant Professor, Teaching Stream in Cell & Systems Biology, starting July 1, 2021. Her experience in designing lab courses and mentoring students will be a valuable addition to our team.

Applying to become a Professor in the middle of a pandemic was an unusual process, so when Sarpal received a meeting request from the Chair after her interview, she accepted with surprise and trepidation. However, when the faces of Chair Nick Provart and Business Officer Tamar Mamourian came onscreen and offered her the job, trepidation turned to excitement for this new phase in her career.

Sarpal started her scientific career in Chemistry at Delhi University, proceeding to a PhD in Molecular Biology at TIFR in Mumbai. She moved to Toronto to study the mechanisms by which adherens junction proteins (AJs) act as a “molecular glue” to bind epithelial cells together to form various tissues that can withstand mechanical forces during animal development.

Sarpal’s greatest research milestone so far resolved a long-standing controversy over how α-Catenin protein organizes the AJ-actin interface and contributes to dynamic regulation of adhesion between epithelial cells. In a recent publication, Sarpal identified mechanisms by which α-Catenin regulates growth pathways that control cell proliferation and cell death. Her work has contributed to an understanding of how AJs impact cancer progression and metastasis.

As a Research Associate in the Tepass lab, Sarpal has guided undergraduate project students for many years. Her advice on fly genetics and experimental design is sought by graduate students, not just in the Tepass lab, but also other labs in the Ramsay Wright building including the Ringuette and Larsen labs.

Sarpal has taught over many years for CSB’s Disciplinary Focus on Stem Cells and Developmental Biology including developing tutorials and training graduate teaching assistants for our Animal Developmental Biology course. She was also a guest lecturer in our Extracellular Matrix Dynamics and Associated Pathologies and Drosophila as a Model in Cancer Research courses. Over the pandemic, she taught online courses along with Professor Ashley Bruce, designing course material including online labs to investigate head and tail regeneration polarity in planarian flatworms and to study pattern formation in the Drosophila larval wing imaginal disc. Her student evaluations were outstanding.

Congratulations on your appointment, Professor Sarpal! We look forward to your contributions in the coming years.

Happy Retirement to Janet and Peggy!

Two of our most experienced colleagues have put up their feet for retirement in 2021. Janet Mannone and Peggy Salmon worked to support thousands of students at U of T for over 35 years each. As Undergraduate Coordinator and Course Administrator respectively, they provided valuable guidance and support to allow TAs and instructors to deliver excellent CSB courses and programs. We look forward to working with Melissa Casco and Nalini Dominique-Guyah, who were trained by Janet and Peggy to take on these roles.

Janet’s work refined the remit of our courses and knit our disparate programs together. She navigated many difficult transitions over her years at U of T; in March 2020, her tenacity and commitment to comprehensive outcomes facilitated the department’s rapid roll out of online teaching.

In a message to students and staff, Janet expressed with much affection that “I cannot fully express how fortunate I have been to have had a job that has brought me so much pleasure first in Zoology, and then in CSB. I will miss our chats and the laughter, but I feel ready to move on.”

Peggy was the recipient of the Outstanding Administrative Service Award in 2017. She put her impressive communication skills to the service of our students, helping them to navigate Faculty policies and regulations with diligence and a great sense of humour. Every instructor trusted that Peggy’s organizational acumen would help them through the chaos of scheduling lectures, assignments and exams.

Peggy started as a research assistant in Zoology in the late Nicholas Mrosovsky’s lab and says that as Course Adminstrator she “was fortunate [to be] given the opportunity of helping students and professors in the undergraduate office. I have a lifetime of memories but I will very much miss the personal connections.”

Both Peggy and Janet provided a personal touch and genuine concern for thousands of undergraduates in life sciences at U of T. They will be greatly missed.

Prof Christina Guzzo guides trainees by following model traits of multiple mentors

Prof Christina Guzzo studies HIV infection in her lab at UTSC and shared with us how she mentors CSB grad students and undergraduates based on the best traits of those who trained her.

Guzzo excelled at sports as a youth and was curious about the way bodies worked and how they stayed healthy, so she pursued a BScH in Life Sciences at Queen’s University. She found her courses engaging, but Guzzo’s PhD supervisor Prof Katrina Gee taught her that science could be fun. When Guzzo performed the first protein separation in Gee’s new laboratory, they danced together in excitement at their first result. This was the point when Guzzo formed an interest to build a career in academia, and an exuberance about science that she now models for her trainees.

Being the first grad student in Gee’s lab meant that Guzzo could not explore wild ideas, but had to ensure that each experiment would support meaningful and publishable progress. This taught Guzzo the importance of establishing a solid groundwork for experiments. With efficiency, Guzzo had a remarkable output of 5 first-author papers by the end of her PhD, and another 6 co-authored works. The week of her PhD defense culminated with running the Boston marathon, giving her 42 kms to reflect on all that transpired in grad school. Indeed, distance running has been a critical element of Guzzo’s career trajectory, an outlet to reflect and think.

Pursuing wild scientific ideas had to wait until Guzzo earned a post-doctoral fellowship at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, USA. She studied HIV infection under the supervision of Drs Paolo Lusso and Anthony Fauci, world-renowned scientists for their contributions to the HIV field. At the NIH, they had all the funding, equipment, and patient samples they needed, so the only limit was their inventiveness.

There were new lessons in mentoring; with these resources came the intense drive to use them responsibly and with the seriousness and urgency that a decades-long pandemic virus required. Drs Lusso and Fauci modelled devotion to science; despite their high-profile positions, emails were responded to in real-time, and research was pushed forward 365 days a year. While not an entirely healthy approach to science, Guzzo learned what is possible when ‘all systems are go’.

In the lab, Guzzo knew that cells respond to viral infection by turning on certain genes. In particular, human integrins were observed to be induced in HIV-infected cells, so Guzzo wanted to know how quickly the integrin protein was turned on in the infected T cells. She was incredulous at her results:”it’s there after one minute!? It’s there one second after infection?!”. Then came her “Aha!” moment: this response was too quick for turning on a gene, so the protein must be present on the HIV virus when it is binding to the cell! With supporting experiments to verify her novel findings, she polished the story with the guidance of Lusso and Fauci, published the work, and used this research as a foundation for her own lab at UTSC.

Although it appears like a seamless career trajectory into academia, the last year of Guzzo’s post-doc was wrought with personal adversity when she experienced the pre-term birth of a child with Down syndrome. Within one day she went from working productively in the lab to sitting at the crib side of her daughter in intensive care for 4 weeks straight. When Guzzo made it back to the lab to finish her post-doc there was a new outlook on life. Family was cemented as a priority for Guzzo, and science came second. Guzzo models this with her students and hopes to be the mentor that shows it is possible for a female scientist to put her family first, but only with adequate support systems, and a lot of hard work.