High school students explore research in biology as a career at CSB

Professor Ritu Sarpal organized a two-day Biology workshop, on Apr 15 and Apr 29, for Black high school students enrolled in the Pursue STEM program in her role as Professor and as a member of CSB EDI committee.

Pursue STEM supports Black high school students interested in STEM fields, and is delivered in partnership with Leadership by Design (LBD), the University of Toronto Office of Student Recruitment, and other Departments within our Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

The workshops were designed to give students a flavor for ongoing cutting-edge research in Biology.

Two-headed flatworms

Professor Sarpal gave a talk on stem-cell mediated regeneration and how planarian flatworms serve as a great model system for studying this process.

For their laboratory work, students used wild type flatworms and experimental flatworms in which a gene called β-catenin was turned down using the dsRNA approach. Students cut their worms on the first day, and then examined the regenerated worms on their second visit two weeks later.

They were extremely excited to see that a piece of the wildtype worm missing both a head and a tail was able to regrow a completely new head and tail in just two weeks.

An even more exciting result for the students was to find that a similar piece obtained from worms lacking β-catenin grew two new heads instead of a head and a tail, highlighting the role of this gene in controlling regeneration.

Hungry roundworms

In a workshop led by Professor John Calarco and PhD student Kailynn MacGillivray (Saltzman lab), students learned about a tiny roundworm called C. elegans. This model organism, affectionately known as ‘the Worm', is widely used in Biology due to its versatility in genetic studies.

Calarco presented a short seminar highlighting the features of C. elegans. The students then acted as geneticists, observing different strains of normal and ‘mutant’ worms and taking notes on their appearance and behaviour.

In a second module, students were asked to time and ‘track’ normal and mutant worm behaviour as these animals foraged towards a food source.

At the end of the workshop, MacGillivray and Calarco held a Q and A session to address any questions from the students about undergraduate and graduate studies in the life sciences at UofT, as well as other questions surrounding career decisions.

When asked to comment about their workshop experience, students wrote:

- “Enjoyable! It made me want to learn more about the regenerative properties of different species and how it can be applied in medicine.”

- “I enjoyed the workshop, it was fun learning about regeneration and questioning if other animals regenerate too. It was my first lab experience and it made me want to have more.”

- “I was not a fan of Biology as I believed it to be less useful than the other two sciences. However, with this workshop I was able to see how broad biology is in terms of species, treatments, experiments and molecular functions. I now want to see how regeneration plays a role in humans especially the eye.”

“It was great to see that such workshops can create a lot of enthusiasm for biology among the high school students,” said Professor Sarpal. “I’d like to thank our graduate students Rebecca Tam and Kailynn MacGillivray, and teaching lab staff Lisa Matchett, Reta Aram, and Pui Tam, for their invaluable assistance with the workshops.”

Keep on moving: paralysis of narcolepsy relieved by chemogenetic cell therapy in mice

Anyone affected by the sleep disorder narcolepsy can experience sudden paralysis that causes them to collapse in the middle of their day, a symptom called cataplexy. Drug treatments for cataplexy are available but must be taken in two doses, one at bedtime and the other in the middle of the night, disrupting sleep. Researchers at the University of Toronto have shown promising results in mice for treating cataplexy with therapeutic cells.

Dr Sara Pintwala of the Peever laboratory in Cell & Systems Biology focused her studies of cataplexy on the neurotransmitter orexin. The daytime sleepiness and cataplexy of narcolepsy occur when orexin neurons in the lateral hypothalamus of the brain either degenerate or fail to produce orexin.

Pintwala collaborated with the Belsham laboratory in the Department of Physiology to grow orexin-expressing neurons in the lab. She engineered these cells so that they were activated to express orexin by a specific chemical, a technique known as chemogenetics. This allowed her to tune the levels of orexin produced by the cell prior to transplantation, reducing the number of mice needed for the experiment.

Cataplexy occurs more often when the affected individuals experience positive stimuli. Pintwala was able to increase observed cataplexy episodes by keeping mice in a social environment with exercise wheels and by including chocolate with their food. She could then test the ability of her treatments to relieve cataplexy in this environment.

Stable patterns of behaviour like sleep and wakefulness are coordinated in the lateral hypothalamus of the brain. Pintwala was demoralized to find that transplanting her engineered orexin-expressing cells into this region failed to restore normal patterns of behaviour in mice lacking orexin. However, she knew that the neural circuits that promote wakefulness and motor behaviours form connections to a separate brain region called the dorsal raphe.

Pintwala felt guarded optimism when she observed that transplanting orexin-expressing cells directly into the dorsal raphe reduced both the number of cataplexy episodes and the severity of cataplexy. Further experiments confirmed relief from the symptoms of cataplexy. Pintwala was certain of her success when she observed that the treated brains showed hundreds of orexin-expressing neurons enervating the dorsal raphe.

Pintwala and Peever’s research, published in Current Biology as “Immortal orexin cell transplants restore motor-arousal synchrony during cataplexy” provides evidence towards the use of cell replacement therapy as a therapeutic strategy for narcolepsy.

The next step in this process will be alleviating the sleepiness experienced by those affected by narcolepsy. This means future experiments will focus on the sleep circuits that impact a region called the locus coereleus as a target for treatment.

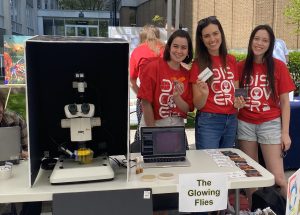

Science Rendezvous was a huge success for CSB!

On Saturday, May 13th, St George Street was shut down in front of the Ramsay Wright Building for Science Rendezvous 2023. CSB was out in force to share research activities in Animals, Plants and Bacteria designed by CSB graduate students, staff and Professors.

On Saturday, May 13th, St George Street was shut down in front of the Ramsay Wright Building for Science Rendezvous 2023. CSB was out in force to share research activities in Animals, Plants and Bacteria designed by CSB graduate students, staff and Professors.

Over four hundred people stayed to engage with us out of the thousands who passed by to take a look. “Several families were translating from English to their mother tongue for their young kids, which was a great mirror of Toronto's diversity,” noted CSB grad student Tatiana Ruiz-Bedoya.

Visitors loved the regenerating flatworms that Professor Ritu Sarpal and Leo Xu showed. Their demonstration showed how gene alterations could make decapitated worms regrow two heads. One young visitor commented "I wish I could have two heads like the mutant flatworms. I would then have two brains and I would be supersmart!"

The movement of tissues during embryo Development was demonstrated by Sirma User with the aid of colourful plaster models and online tools. “A few people (even some kids) wondered about what happens if we take a group of cells and try to grow them outside the embryo,” User recalls, “This is the kind of insightful question we expect from our upper year students and led to some detailed discussions.”

Developmental Biology was further exemplified through the “Glowing Flies” activity created by Gordana Scepanovic and Veronica Castle. Using a fluorescence microscope, visitors could see glowing GFP-tagged fly embryos. They also looked at living flies in glass vials: “Kids definitely loved making the flies with the temperature sensitive Shibire mutant pass out by warming them up with their hands!”, observed Scepanovic.

Developmental Biology was further exemplified through the “Glowing Flies” activity created by Gordana Scepanovic and Veronica Castle. Using a fluorescence microscope, visitors could see glowing GFP-tagged fly embryos. They also looked at living flies in glass vials: “Kids definitely loved making the flies with the temperature sensitive Shibire mutant pass out by warming them up with their hands!”, observed Scepanovic.

Our research in Neuroscience was represented by Dr Melissa Seranilla and Haushe Suganathan, who attached electrodes to visitors to show them the signal travelling from their brain to the muscles of the arm.

Dr Neil Macpherson presented artwork created for the department, including cell biology images, and paintings and jewelry inspired by research in gene expression.

Stem Cell Biology was explored by Tiegh Taylor and Nawrah Khader. They designed a marble run with marbles representing tissues developing from stem cells. Changing the flow of marbles with pegs or barriers representing certain proteins caused the marbles to gather in a bin representing specific organs. “We showed visitors that that our bodies are amazing at using stem cells during development to create complex organs” says Taylor. ”We told them that the better we understand that process, the closer we are to being able to regrow organs in a lab.”

Dr Zoe Gillespie and Shanelle Mullany showed how DNA is extracted by having visitors mush up banana in a plastic bag and making the banana DNA crystallize in the bag. This led to discussions of the importance of DNA for research in Genomics and Computational Biology.

Professor Heather McFarlane created a poster on Plant Biology detailing how cell walls protect, support and hydrate plants. The poster contained activities visitors could use at home to see cell walls in celery. Kathryn McTavish and Tatiana Ruiz-Bedoya displayed some fascinating plant specimens from our teaching collection, and discussed their research in plant immunity by showing the effects of bacterial infection in plants.

Imaging specialist Dr Kenana Al Kakouni showed microscope slides of animals, plants and bacteria to reveal the diversity of Cell Biology, and provided stickers of striking cell images. Visitors were impressed by the degree of magnification our microscopes displayed.

Using plastic models and diagrams, Natalia Gajewska and Sofia Karter encouraged our younger visitors to make organelles out of modelling dough, fuzzy balls and pipe-cleaners. They explained the role of individual organelles, such as chloroplasts using sunlight to make sugar, and mitochondria breaking down sugar to make ATP to fuel the cell. As small hands busily worked, Gajewski and Karter used follow-up questions from kids and parents to discuss Departmental research.

Using plastic models and diagrams, Natalia Gajewska and Sofia Karter encouraged our younger visitors to make organelles out of modelling dough, fuzzy balls and pipe-cleaners. They explained the role of individual organelles, such as chloroplasts using sunlight to make sugar, and mitochondria breaking down sugar to make ATP to fuel the cell. As small hands busily worked, Gajewski and Karter used follow-up questions from kids and parents to discuss Departmental research.

Thank you to our presenters for their amazing work designing exhibits, engaging with our visitors and getting them excited about Cell & Systems Biology!! We are also grateful for the hard prep work done in advance by Samuel Delage, Fernando Valencia, Lisa Matchett, Anna Koselj, Alice DesRoches and Tom Gludovacz.

See you next year at Science Rendezvous!

CSB Researchers earn multiple NSERC awards

Congratulations to Professors in CSB who earned NSERC Discovery and NSERC-RTI grants!

NSERC Discovery Grants

The Discovery Grant program supports ongoing programs of research with long-term goals. These grants recognize the creativity and innovation that are at the heart of all research advances.

Professor Dorotea Godt will probe the “Function of cadherins in microvillus morphogenesis”.

Professor Tony Harris will examine “Roles of plasma membrane folds in the assembly and function of cortical cytoskeletal domains during syncytial Drosophila embryogenesis”.

Professor Qian Lin will “Study the neural mechanisms of reward-based decision making by whole-brain single-neuron recordings in behaving zebrafish”.

Professor Shelley Lumba will use her funding to determine the “Evolution of signalling networks in germination of parasitic and nonparasitic plants”.

NSERC-RTI Grants

RTI grants are the primary avenue for university researchers to obtain support for costly research tools and instruments

Professor Dinesh Christendat will be able to purchase high capacity protein expression and production incubators for his structural biology approaches to understand the functional divergence and regulation of metabolic proteins in plants and microbes.

Professor Jennifer Mitchell will update her transcriptional regulatory element functional genomics equipment.

Professor John Calarco will use his funds for upgrades to an essential imaging platform at our multi-user microscope facility.

Professor Sergey Plotnikov will have the funds to purchase an illumination source for high-resolution live-cell imaging system.

Congratulations to our researchers and thank you to NSERC!

Benign bacteria can cooperatively cause virulence

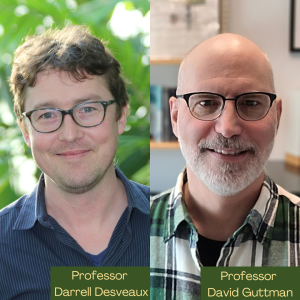

“In science, we often focus on a single ‘wild type’ organism, but even a single species of bacteria has as much variation as the instruments in a symphony. The French Horn produces a lovely sound, but if all you do is focus on French Horn, you’ll never know the joys of a symphony.” This is how Prof Darrell Desveaux of Cell & Systems Biology explains his approach to studying virulent bacteria.

Desveaux and his colleague Prof David Guttman study plant infection by the Pseudomonas syringae bacteria. Their “systems-level” approach takes into account the natural diversity of this species. In a new study published in Nature Microbiology, they find that distinct bacteria living in a community are collectively able to provoke disease without any single bacterium being the cause.

Desveaux and his colleague Prof David Guttman study plant infection by the Pseudomonas syringae bacteria. Their “systems-level” approach takes into account the natural diversity of this species. In a new study published in Nature Microbiology, they find that distinct bacteria living in a community are collectively able to provoke disease without any single bacterium being the cause.

Graduate student Tatiana Ruiz-Bedoya conducted these experiments in the Desveaux and Guttman labs. “I find it fascinating that P syringae is found wherever there is water, including in clouds and snow. The versatility of P syringae to survive in each of these ecological niches makes it a species complex with different evolutionary pressures in each niche.”

The most consequential niche to humans is within plant leaves, which can be infected by P. syringae to extract extra resources that help the bacteria grow. “The community of P syringae researchers is a huge benefit for us,” asserts Guttman, “The genomics, ecology, and pathology are well-established, and the resources and tools we have developed make the system easy to manipulate. The insights we gained in this study would not be currently possible with any other plant or animal pathogen..”

Infection carries risk for the bacteria since they must evade the immune system of the plant host. P. syringae employs a diverse array of “effector” proteins to support bacterial growth (virulence) by suppressing the plant immune system. This new research assesses the ability of effectors from separate individuals to work in concert in causing virulence in the plant Arabidopsis.

The commonly used Pst strain DC3000 has 36 effectors. Ruiz-Bedoya started with a strain that is non-virulent due to its lack of effectors. She created a 'metaclone' with one effector per bacteria in a culture that contained all 36 effectors. Each individual strain of bacteria in the metaclone is non-virulent, but she hypothesized that effector functions within the community of bacteria would drive the emergence of virulence in the invading population.

When Ruiz-Bedoya sprayed her metaclone on Arabidopsis leaves, the effector metaclone was indeed virulent, demonstrating the cooperative benefit of this approach to evading the immune response for the bacterial community. She then tested the effect on the community of adding a single strain that provoked an immune response. She found that growth of all bacteria was suppressed. Effectors can thus act as against the community when they trigger an immune response.

Desveaux is excited by how this revelation changes our view of virulence. “You can have a single pathogen that is a one-man band of virulence, but we’ve shown that virulence can come from a symphony of individually ineffective strains that together cause virulence and evade immune detection.”

The full details are available at "Cooperative virulence via the collective action of secreted pathogen effectors"

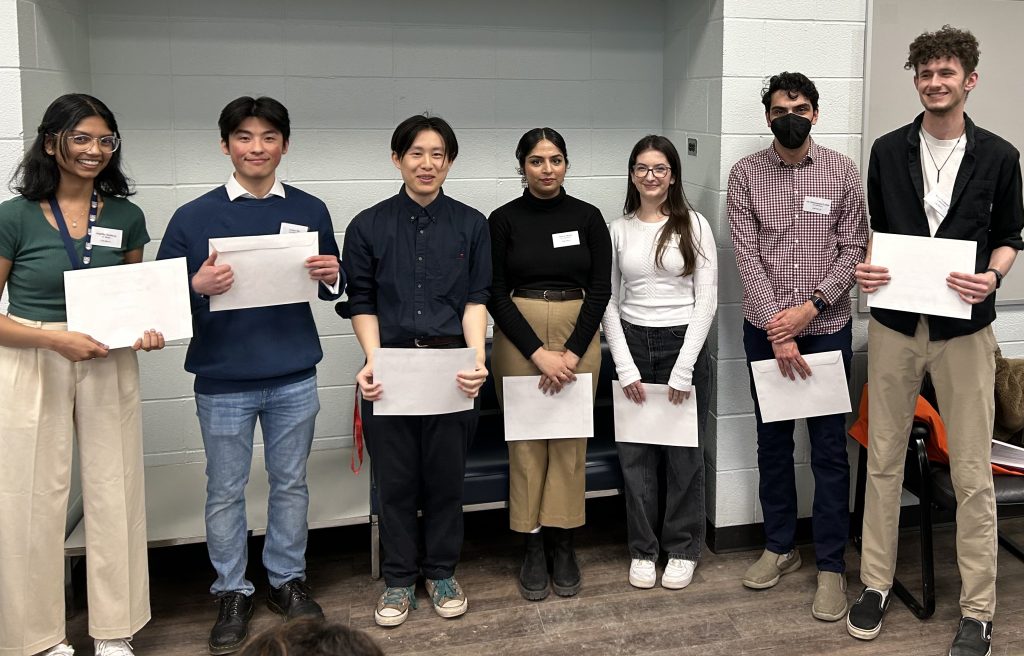

Oustanding CSB educators earn 2022-23 TA Teaching Awards

Congratulations to the recipients of the 2022-23 CSB TA Teaching Excellence Award! This award recognizes the significant role of Teaching Assistants in the Department of Cell and Systems Biology and their key contributions to the learning experience of students.

This year, the award was earned by graduate students Kevin Xue (CSB350), Tatiana Ruiz-Bedoya (BIO260) Christine Nguyen (BIO130/230) and Ernest Liang (BIO130) based on feedback from undergraduate students in their tutorials.

“I was surprised to learn I was chosen for this award, and grateful that the students showed this faith in me” remarks Nguyen. She confides that she vividly remembers what it was like to be in first year and tries to apply that experience to her teaching.

“I am also grateful” says Xue. “I enjoy working with the students as a TA and it makes me glad to see how their comprehension of the subject grows over time.”

Liang observes that teaching is beneficial for him as well as for his students. “The class is coming to the field fresh so they ask unexpected questions of surprising depth. In formulating a comprehensive answer, I come to understand the topic in a deeper way.”

Ruiz-Bedoya notes of her students, "This course is their first contact with most concepts in genetics so it is inspiring to see their dedication and devotion to learning them in such depth, it makes it all the more fun to find new ways to help them.”

TAs are nominated by undergraduate students enrolled in their course and evaluated based on the following criteria:

• Demonstrates a keen interest and enthusiasm towards teaching and learning

• Ability to effectively organize, structure and facilitate learning in the classroom, tutorials or labs

• Actively engages, motivates, and challenges students

• Uses teaching practices that advance accessibility, equity, diversity, and inclusion

• Demonstrates depth of knowledge in the subject and effectively communicates complex concepts to students

• Utilizes innovative teaching strategies and tools

• Provides timely and constructive feedback to students

Congratulations to these outstanding educators!

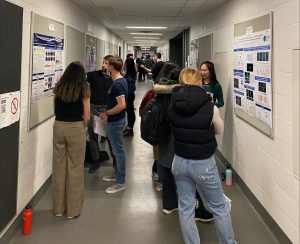

CSB project students present their year's work in research

A year of research by CSB project students culminated in a poster session on March 31st, 2023. The students used the posters to describe their research and results, while answering questions from peers and professors. This presentation represents the final step of their CSB497/498 course.

A year of research by CSB project students culminated in a poster session on March 31st, 2023. The students used the posters to describe their research and results, while answering questions from peers and professors. This presentation represents the final step of their CSB497/498 course.

Presentations were assessed based on the descriptions given by students and on the ability of students to respond to questions. Outstanding presentations were awarded the F Michael Barrett award. Undergraduate Chair Dinesh Christendat revealed that "It was a challenge for the judges to assign these awards, since all the presentations were impressive."

Angitha Mriduraj studied "Characterizing the Impact of Camsap2a Knockout on Patterning genes during Zebrafish Epiboly" in the Bruce lab. The Bruce lab studies how the complex and varied body plans of animals are generated during embryonic development.

Arthur Siu studied how "Intracellular Calcium is Necessary for Viscosity-dependent Cell Migration" in the Plotnikov lab for his award. The Plotnikov lab aims to uncover how migration of animal cells is controlled by mechanical signals form the extracellular environment.

Yutei Shi earned his award for "From Enhancer Sequence to Function: Validating Novel Neural Network Predictions on Contribution of Motifs and Motif Copy Number" in the Mitchell lab. The Mitchell lab studies how the genome functions in stem cells to regulate self-renewal and differentiation.

Smera Mehta worked on "Testing a new single copy transgenesis method in C. elegans" in the Calarco lab to earn her award. The Calarco lab studies post-transcriptional gene regulation in the nervous system.

There were two awards for research in the Saltzman lab which studies the role of chromatin regulation in establishing and maintaining the gene expression differences that underlie cellular identity. Sofia Eiras earned her award for "Histone H2A monoubiquitylation by Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 in C. elegans nervous system development" and Aly Muhammad Al-Karim Ladak won for "Guardians of the epigenome? The role of the histone methylation readers CEC‐3 and CEC‐6 in heterochromatin establishment and repetitive element silencing".

Evan Berthelot earned an award for research in the McFarlane lab on "Investigating the Role of Auxin in Cell Wall Synthesis". The McFarlane lab researches plant growth and development and the fundamental mechanisms by which plants sense their environment and adjust their growth in response.

Congratulations to everyone who came out to present, and especially to our outstanding award winners!

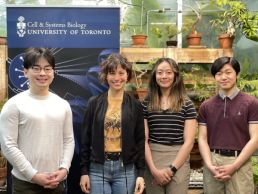

Pursue STEM provides an introduction to Cell & Systems Biology for Black high school students

Professor Ritu Sarpal, the CSB Liaison for Pursue STEM, organized an outreach event on March 14th as part of our EDI committee’s efforts to encourage minority groups to pursue higher education in the biological sciences. Pursue STEM is a program that supports Black high school students interested in STEM fields which is delivered in partnership with Leadership by Design (LBD), UofT’s Office of Student Recruitment, and other Departments within the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

As part of this event, high school students were introduced to ongoing cutting-edge research activities in CSB via short talks and a tour of our imaging facility, following which they visited the Calarco, Plotnikov, and Harris labs (as shown above, in order). Kudos to our graduate students, Jeffery Stulberg, Pallavi Pilaka, Bina Sugumar, Ernest Iu, Fernando Valencia, Leo Xu, Vanessa Ghorayeb, and scientific staff members, Dr. Kenana Al Kakouni, and Audrey Chong, who made this event a big success!

When asked to comment about their CSB department visit, students responded:

"I really enjoyed the visit to the CSB department. I found it very engaging and interesting. The range of research topics and methods was cool and exciting. It was very inspiring."

"I most enjoyed the molecular biology lab [Plotnikov lab] and observing the worms under the microscope [Calarco lab]. All of the facilitators were so helpful and fun too!"

"I learnt a lot about the different types of model organisms. I most enjoyed viewing fibroblasts under the microscope [Plotnikov lab] and looking at fruit flies [Harris lab]"

"Events like this could help to encourage minority groups to pursue higher education in the biological sciences," says Professor Sarpal, who is also conducting two hands-on workshops in April for Pursue STEM students to perform regeneration experiments on flatworms.

Janssen Award for Equity and Inclusion to improve opportunities for CSB graduate students

CSB is grateful for a new endowment to U of T from Jannsen Canada that will help address health inequity and provide ongoing support to future leaders in healthcare.

The Janssen Award for Equity and Inclusion supports Faculty of Arts & Science undergraduate and graduate students, with a focus on Black and Indigenous students.

"Janssen's endowment serves a crucial role in fostering a community in which learning and scholarship can flourish," says CSB Chair Nicholas Provart. "We are glad for this opportunity to allow future generations - regardless of background - to seize opportunities in Cell & Systems Biology"

The graduate award supports a PhD student in the Department of Cell & Systems Biology based on academic merit and financial need, while the undergraduate award in the Human Biology Program is based on financial need.

Professor Kenneth Yip teaches many first year undergraduates and is Chair of CSB's EDI Committee. “We recognize that promoting equity and inclusion in our department is essential to achieving our mission," says Yip, "This endowment will help create a more diverse and inclusive learning environment that supports the success of all students.”

You can read more about this important endowment in "Janssen Funds for Equity and Inclusion will help remove barriers to education"

Important tips on communicating with your busy Principal Investigator

Professors are passionate about their research topic and the trainees who do the experiments are key, but supervision must compete with all their other responsibilities. These "Principal Investigators" need to write grants for research money, budget for spending their funds on research, write up the results of their research, teach large classes, and help run the University.

Ben Tsang is an experienced lab manager and now a first year CSB grad student in Prof Robert Gerlai's lab at University of Toronto Mississauga. In the Careers section of Nature Magazine, he shared his advice on efficient communication with your busy supervisor. You can read more through this link.

Congratulations on this article, Ben!